Climate Justice and the Leap Frog

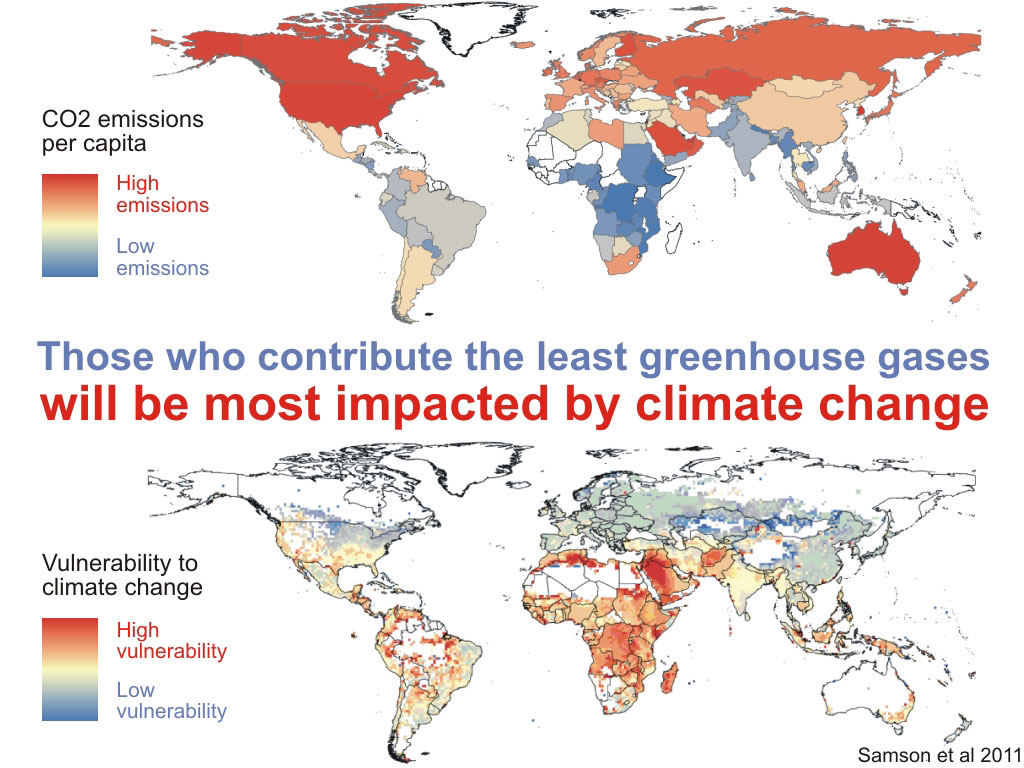

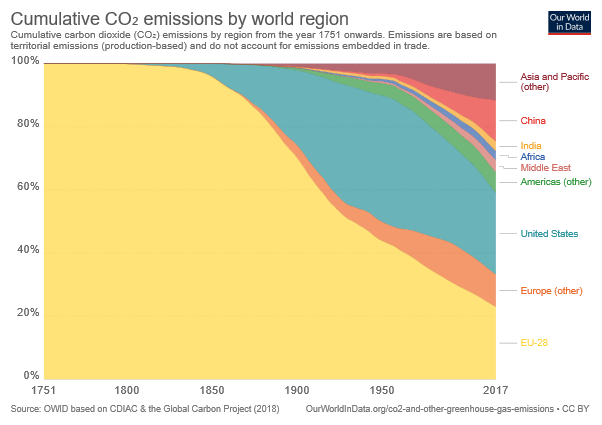

- 8 minsThose who contributed the least to climate change will be the most impacted by the consequences of climate change. Research going back to 2011 highlighted this (see first figure below) with scientists from Mcgill University developing the Climate Demography Vulnerability Index which takes into account how regional climate will change but also local population demographic changes. High vulnerability is predicted for regions where a decline in climate conditions currently supporting high population density is combined with rapid population growth (Samson et al., 2011). Highly vulnerable areas include Central and South America, the Middle East, Eastern and Southern Africa and parts of Asia. Contrast this with the lower figure illustrating the CO2 emissions per capita for these nations. The blue, less polluting regions in this map are the same red regions in the vulnerability map. The contrast is even more drastic when considering cumulative emissions over time (second figure below) with the vulnerable regions representing just a small fraction of cumulative emissions compared to North America and Europe. These vulnerable regions are made up of the poorer countries of the world who do not have economic means or infrastructure, that the more developed countries possess, to mitigate the impacts of climate change (Mendelsohn et al., 2006). The trifecta of most vulnerable, lowest emissions and economically the poorest. Climate change is a global problem, from which a contribution from any region of the world affects its entirety. There is injustice in the fact that those who have contributed and continue to contribute the least to climate change, are the ones who will suffer the most detrimental consequences.

Top: National average per capita CO2 emissions based on OECD/IEA 2006 national CO2 emissions (OECD/IEA, 2008) and UNPD 2006 national population (UNPD, 2007). Bottom: Vulnerability Index from Samson et al. (2011), where red shows regions that are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Reproduced from Skeptical Science Graphics

Top: National average per capita CO2 emissions based on OECD/IEA 2006 national CO2 emissions (OECD/IEA, 2008) and UNPD 2006 national population (UNPD, 2007). Bottom: Vulnerability Index from Samson et al. (2011), where red shows regions that are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Reproduced from Skeptical Science Graphics

Cumulative CO2 emissions by world region (Our World in Data, 2018)

According to Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland and current Chair of the Elders, Climate Justice is about "linking human rights and development to achieve a human-centred approach, safeguarding the rights of the most vulnerable and sharing the burdens and benefits of climate change and its resolution equitably and fairly". Fridays for future and mass protests by school children have started to create awareness on the intergenerational injustice of climate change. However, those who are most vulnerable, the poor, the disempowered and the marginalised, are often forgotten and the climate discourse often fails to capture the needs and stories of these people. This leads us to an ethical problem, how do we protect those vulnerable to our actions and unable to hold us accountable?

As a participant of the EIT Climate-KIC Journey Summer School, a core component of the summer school was applying principles of systems thinking within a group in a project of our interest. Our diverse team of four was made up of Bianca, born in the Amazon rainforest region of Brazil and currently a student in sustainable development in Utrecht, Mark, US American but with an extensive background in international development working primarily in the Global South and Mathilde, born and raised in the beautiful South Pacific community of Noumea (To find out more about these incredible people, check out their bios here!). We formed a team based on our core shared value of climate justice. Spending three weeks of the summer school together working on our project, it was very fascinating to hear about their own experiences growing up in different parts of the globe and yet how many similarities and shared values existed between us. From our experience in our own regions, we have seen that there is huge motivation from youth to become changemakers and tackle climate change. Our team was lucky to be studying in Europe and get the opportunity to participate in a programme such as the Journey. We saw it as an injustice that youth from the Global South do not have this opportunity. This led us to our problem statement:

"There is a lack of accessible opportunities and networks for youth of the global south to become changemakers in their local communities in the fight against climate change"

The Climate Justice League Team (From Left to Right: Anjukan, Bianca, Mark and Mathilde)

The Climate Justice League Team (From Left to Right: Anjukan, Bianca, Mark and Mathilde) Within our group, all of us, through our experience, have come across the preconception that knowledge transfer needs to be from the Global North to the Global South and we even observed this during the Journey talking to certain people. However, the concepts which work in some regions may not be applicable to others, and people know best their own contexts. We really wanted to come up with a solution that was for the Global South from the Global South all the while ensuring climate justice as a core value. There is a lot to learn looking rather than at technology but at the local and traditional sustainable practices that have been the hallmark of the people and communities of the Global South but that are now at risk in a "Western-looking" world.

Take the humble banana leaf, traditionally it was used to serve and eat food off in the part of Sri Lanka that I come from (also commonly used in other parts of the world such as South India, South East Asia and Central America for cooking and serving purposes) and now it is generally just reserved for festive occasions. It's becoming harder and harder to find places in Jaffna that serve the traditional rice thali off a banana leaf. Whilst visiting the MakerSpace at UnternehmerTUM (Centre for Innovation and Business Creation at TUM), I came across Leaf Republic, a start-up founded at the MakerSpace. They make disposable plates, made from the leaves of the wild creeper plant sourced from Asia and South America, which are 100% biodegradable. Our ancestors and traditions have a lot to teach us. The traditional values of indigenous peoples such as the Māori of New Zealand revolve around their wellbeing being invested in the wellbeing of their environment in both spiritual and physical ways and that the wellbeing of one depends on the wellbeing of all. They also hold a strong sense of responsibility of intergenerational equity, with practices guided on the principle of how one's action will affect the wellbeing of past and future generations. An example is the rāhui, a prohibition or setting aside of a place for a specified time, for example, a fishing ground to either conserve endangered species or protect the fishing ground from overfishing. For the Maori, fishing was both a practical and spiritual activity. These values and associated practices and knowledge are considered dying and are not at the fore of the fight against climate change. How can we change this? Our group believes in the power of education and mindset shifts. We want this to be an integral part of the solution that youth in the Global South can champion.

Top: Traditional Rice Thali of Jaffna, Sri Lanka (Photo used with permission from Spinthewindrose). Bottom: Disposable Plates Made by Leaf Republic, originally a start-up at TUM

To understand our use group, we conducted a user needs survey tapping into our connections in the Global South. We were blown away with the level of interest shown and the amount of responses we got within two days. There are a lot of interesting insights from the survey results and given that this blog is quite long already, I will save this and the solution we eventually developed for the next blog (or you can go here to read our report we had to submit). In the Iceberg model of systems thinking, changing mental models is at the tip of the iceberg with the most leverage. So why don't we think of the Global south as sustainability champions and not as 'developing nations'? Imagine how empowering this would be for youth from these countries. There is a massive opportunity for the Global South to "leap-frog" the practices of the Global North that we are now acknowledging as leading to the degradation of natural environments and contributing to climate change. If this could be achieved, I think this would be some form of climate justice. To finish this blog however, I would like to finish with a question for you. What are the values you live by in your life?

Image credits: Cover - Reproduced from [Skeptical Science Graphics]

References

- Samson, J., Berteaux, D., McGill, B., Humphries, M (2011). Geographic disparities and moral hazards in the predicted impacts of climate change on human populations. Glob Ecol Biogeogr, 20:532–544.

- Mendelsohn, R., Dinar, A., & Williams, L. (2006). The distributional impact of climate change on rich and poor countries. Environment and Development Economics, 11(2), 159-178.