So what exactly am I researching?

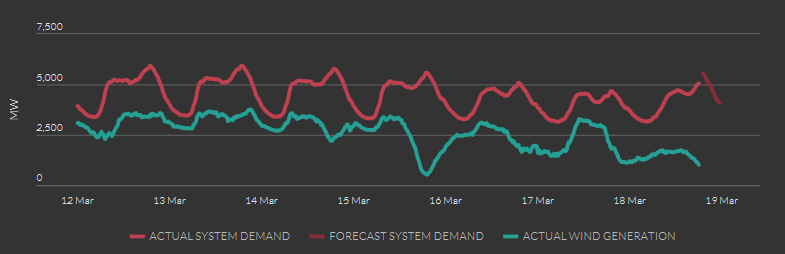

- 8 minsWe humans are creatures of habit. And most of our activities consume electricity in some fashion. Consequently, our electricity consumption shows a very similar trend, day in day out. To illustrate this, I found the Ireland All-Island system demand for the last week and this is illustrated in Figure 1 in red. This is typical of most electric grids worldwide with the evening peak load caused by a lot of people turning lights on, boiling kettles, and streaming Netflix, all at the same time.

Traditionally, this peak demand has been easy enough to meet with additional fossil fuel power plants being brought online to cover this. The future, however, is large amounts of renewable energy sources powering national grids. New Zealand is blessed with abundant hydroelectricity, both renewable and controllable to some extent. The story is different in Ireland, with wind generation being the most common resource. The actual wind generation for Ireland is shown in green in Figure 1. This figure actually shows that at some points, wind production was "curtailed" (turned off or set to produce less electricity) as the demand was not high enough (particularly during nights). Wind and solar are variable and intermittent and cannot be controlled in the same way as fossil fuel based power plants. This poses a supply and demand balancing issue and this mismatch, not managed, can lead to crippling the entire power system - think blackouts and the associated damage. To tackle this, current norms are to turn on additional power plants (or peaking plants) to meet the extra demand and curtail wind production respectively. Increasingly, managing the demand as a means of balancing the system is being considered as a more environmentally friendly and economic solution. Demand response is one facet of Demand Side Management (DSM) and is the change in power consumption of a customer to better match the demand with the supply. The customer is usually incentivised or paid to do this - think about it, paying a user to reduce their consumption can be more cost-effective than having to turn on a power station just to meet an additional load.

Buildings represent 40% of final end-use energy consumption by sector [1]. So, how can buildings be more flexible with their electricity consumption? A significant portion of the building energy spend goes towards making sure us occupants are thermally comfortable. This is done using heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems. Using the thermal mass effect (essentially any mass stores heat to a certain extent - so the walls, floor and air can be used as a sort of heat storage), a heating or cooling load can be shifted or decreased/increased with occupants barely noticing. Humans have known about thermal mass for a long time and put it to good use. For 1000's of years, people in hot desert climates have used thick mud walls for their huts to absorb the heat during the day (and keep the interior cool) and then release this heat inside during the colder night. In today's context, the heating thermostat can be turned up a notch when there is plenty of supply and the thermostat can be turned down a notch or turned off completely when supply is scarce. Other sources of this flexibility in consumption are through the use of thermal energy storage, electric batteries and use of on-site generation (such as solar PV or diesel generators). So we can define building energy flexibility as "the ability of a building to manage its demand and generation according to local climate conditions, user needs and energy network grid requirements" [2]. My research focuses on commercial buildings - these often feature all of the sources of flexibility mentioned above, are significant consumers of electricity (a single commercial building may consume as much electricity as thousands of homes), and often feature energy management systems which can be used to control the building and receive signals from the grid.

Figure 2: Traditional mud huts using principles of thermal mass (Image source)

Figure 2: Traditional mud huts using principles of thermal mass (Image source)

To automate this and do this efficiently while ensuring occupants of these buildings aren't too hot or cold as a result of any kind of load shifting, we need mathematical models to model and describe the behaviour of the building (and in particular the internal temperatures) to changes in heating or cooling loads (and change in power consumption). This is only half of the solution, you also need control strategies to actually operate and tell the building what to do. Most building control today is actually quite simple, basically based off a series of "if this-do this" rules. Model Predictive Control (MPC) has attracted a lot of research lately as a replacement to these traditional "rule-based control" strategies. MPC is able to take into account a model of the building and use predictions of future disturbances such as weather and inputs such as the price of electricity to optimise the control actions of the building. For every time step of the control, an optimisation problem is formulated to minimise a certain quantity (e.g. energy or cost) given a mathematical model describing the behaviour of the building, constraints on the problem (e.g. the temperature of the rooms have to be within a comfortable limit) considering a finite time horizon into the future. The optimal sequence of control actions (e.g. what temperature setpoint to use) over this horizon is calculated through solving the optimisation problem. The control action for the first time step is applied to the building and the whole procedure is repeated at the next time step with the new inputs and measurements for the new time window. For this reason, MPC is also called receding horizon control. MPC has shown a lot of promise in intelligent control of a building to minimise energy consumption and energy costs for building owners from a research perspective [3].

However, MPC has largely been constrained to academia to date and has not made a successful transition to market in real buildings [4]. The problem stems from deriving the model required in MPC to describe the behaviour of the building. First of all, no one building is the same. Unlike in the automobile or aerospace industries, every building is constructed differently, has different systems and more importantly is operated differently by different occupants. This means that a model generated for one building cannot be simply transferred over to another building. In such "physics-based models", there is a significant cost and effort required to capture required information about the building such as materials, geometry and occupancy patterns. In order to guarantee a solution to the optimisation problem, the problem needs to be "convex" - this term is used in mathematics to indicate that the function you are dealing with is convex - one that always curves up. With buildings being highly complex and non-linear in their behaviour, the challenge of creating a suitable and accurate model are serious hurdles to the widespread implementation of MPC.

Just as AI and machine learning is revolutionising industries from transport to the hospitality sector, so to is it starting to be recognised in building control. Data-driven approaches to MPC where machine learning is used to model the building as a 'black box' and a cyber-physical system show promise in removing the expense of deriving a first principles and physics based model. There are challenges with this: black-box models are often not suitable for control when they are highly non-linear and quality data is required for each building to train the model. The aim of my PhD is to develop a data-driven approach to the modelling and predictive control of commercial buildings that will unlock its inherent energy flexibility. I hope I will develop a scalable method that can be easily applied at scale to commercial buildings with little or no hardware or equipment additions and do my part in enabling a more sustainable built environment.

This is the first of several blogs on my research and I plan to add updates shortly with more details about my research and some of the results. I'd really appreciate any feedback or thoughts and suggestions - both on my research and writing skills!

References

- Marina Economidou, Jens Laustsen, Paul Ruyssevelt, and Dan Staniaszek. Europe’s Buildings Under the Microscope. Tech. rep. Buildings Performance Institute Europe (BPIE), 2011, p. 130.

- Søren Østergaard Jensen, Anna Marszal-Pomianowska, Roberto Lollini, Wilmer Pasut, Armin Knotzer, Peter Engelmann, Anne Stafford, and Glenn Reynders. “IEA EBC Annex 67 Energy Flexible Buildings”. In: Energy and Buildings 155 (2017), pp. 25–34. issn: 03787788. doi: 10. 1016/j.enbuild.2017.08.044. url.

- Serale, G.; Fiorentini, M.; Capozzoli, A.; Bernardini, D.; Bemporad, A. Model Predictive Control (MPC) for Enhancing Building and HVAC System Energy Efficiency: Problem Formulation, Applications and Opportunities. Energies 2018, 11, 631.

- Gregor P. Henze. “Model predictive control for buildings: a quantum leap?” In: Journal of Building Performance Simulation 6.3 (2013), pp. 157–158. issn: 1940-1493. doi: 10.1080/19401493.2013. 778519 url